Throughout the Arab world, young people are rejecting classical Arabic in favour of a mish-mash of English and their own local dialects – ‘Arabish’ – a popular chat language that mixes the two, writes Nick Leech.

When Jihad El Eit opened the first branch of his fast food business in Dubai, he relied on little more than gut instinct when it came to choosing a name. At the time, ‘Man2ooshe & Co’ seemed like an inspired choice. Not only did it fit with the company’s contemporary take on traditional Arabic street food but it also used the Arabic chat alphabet in its name, a phonetic mish-mash of Arabic sounds and Roman characters that has become one of the most common and convenient modes of written communication for Arabic-speaking youth.

In the phonetic Arabic chat alphabet, ‘Man2ooshe’ becomes ‘Man’oushey’ because the ‘2’ is used to represent a pause between syllables in Arabic. The name spoke directly to the young, hip, Arabic but English-speaking market Jihad El Eit was aiming for.

Unfortunately, ‘Man2ooshe & Co’ soon became the victim of its own success, as non-Arabic speakers, unfamiliar with the phonetic transliteration that defines the Arabic chat alphabet, also started to demand the firm’s home-made take on traditional Middle Eastern snacks such as manakeesh, burek, and minikeesh.

“We never expected a non-Arabic audience to be interested in our food,” explains El Eit. “As more Western and Asian customers started coming to our stores, they didn’t understand what the ‘two’ meant. Some people started calling us ‘mantooshey’. Some people thought we were called ‘man-two-ooshey’. The name started to distract from the essence of the brand.”

Three years and five Man2ooshe stores later, El Eit wanted to expand his business further, but felt he had no choice but to employ the services of a consultancy to remedy the issue surrounding the brand’s name. The result was what the chief executive now describes as a “costly facelift”. ‘Man2ooshe & Co’ became ‘Man’oushe Street’ and no longer employs the Arabic chat alphabet in its branding, menus or signage.

“We didn’t do our homework properly when we started in terms of acceptance of the brand,” El Eit explains. “If we had used a generic texting message that was understood by all audiences, I don’t think we would have changed our name, but we used an Arabic word with a twist of English and that created confusion. I regret it now because I paid much more for the rebrand than I did when we started.”

While El Eit’s experience may provide a salutary business lesson for companies targeting non-Arabic speakers, the exponential growth of the Arabic chat alphabet since the 1990s has led to a sea change in the way the language is written by young people across the Arabic-speaking world. Arabish or Arabizi (a contraction of Arabic and Inglizi) even appears in advertising and on TV, especially on youth-oriented shows and channels such as Na3na3 on MTV Middle East. Throughout the Arabic speaking world, Arabish has become a default for written communication among the young in text messages, in email and online.

The preponderance of Arabish in the digital realm should come as no surprise. The language was born online during the 1990s, when operating systems, web browsers, personal computers, keyboards and keypads were unable to support Arabic.

The only readily available option at the time was to use the Roman fonts and characters defined by the American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII), a character-encoding scheme based on the English language that defined the 128 characters – including the numerals 0-9 and the letters A-Z – that appear on printers, keyboards, computers and communication equipment. Originally developed for telegraphic communication, ASCII soon became the effective lingua franca of the internet, a huge benefit to languages written in Roman script, but a massive problem for the users of different alphabets.

Arabic speakers responded to the absence of Arabic script in two ways: some used English, but many more began to use Roman characters to recreate the appearance and the sounds of Arabic words. Arabic was effectively ASCII-ised so that it could be written on a standard keyboard, and numerals were enlisted to represent specific Arabic sounds that do not occur in English. The number 5 became kha; 6 became taa; 8 qa and so on. It was from this ingenuity and the desire to communicate that Arabish was born.

David Palfreyman, a linguist based at Zayed University in Dubai, was the co-author of a 2003 research paper, A Funky Language for Teenzz to Use: Representing Gulf Arabic in Instant Messaging, one of the first academic studies of ASCII-ised Arabic. Palfreyman had arrived in the UAE in 1999 and soon became interested in the way the university’s female students were making use of technology and social media to express themselves.

“I’m interested in the creative aspect of ASCII Arabic and how the issue is playing out in a society that is changing,” Palfreyman explains. When the linguist conducted his research back in 2003, he had no way of knowing just how successful and pervasive ASCII-ised Arabic would become. Not only has it survived the introduction of technologies that now support the Arabic language, but it has thrived.

“Students could write in Arabic now, but I still find lots who continue to type in Roman script. In theory, the technical reasons for using ASCII-ised Arabic have disappeared, but the fact that it has survived shows there must be other reasons for its use.”

Palfreyman believes that ASCII-ised Arabic is not only an important expression of youth culture but that its use of Arabic, English and Roman characters also allows it to act as an identity marker that simultaneously references global, non-Arabic norms. It also gives a voice to the very local Emirati dialect.

“In Emirati Arabic there is a ‘ch’ sound in words like ‘kitabitch’. It’s the feminine form of ‘your book’,” the linguist explains. “In standard Arabic, the same word would be ‘kitabuk’. There’s no normative way in the Arabic script … to write ‘ch’, whereas English has an accepted way of writing that sound. The use of the English ‘ch’ allowed the student in my study to write in the way that she spoke.”

Palfreyman also believes ASCII-ised Arabic contributes to literacy by encouraging reading and writing, but admits he takes an optimistic view of an issue that has become something of a moral panic throughout the Middle East. Instead, there is a widespread and growing perception that classical and modern standard Arabic – the official language of government, news and the Quran – are in a state of crisis.

An increasing number of column inches have been dedicated to the apparent rejection of standard Arabic by the younger generation, while concerned parents have added fuel to the debate by voicing their concerns about the standard of Arabic teaching and the seeming inability of their children to master even basic Arabic skills. Their fears appeared to be confirmed by the findings of a recent report, issued by Dubai’s Knowledge and Human Development Authority, which showed that over the last five years, students in the emirate’s private schools had shown little or no improvement in the language.

Educational experts may identify outdated teaching methods and a reliance on rote learning as reasons for the current malaise, but there is also a widespread perception that the increasing use of English in schools and the popularity of Arabish are also to blame.

“Arabish started with our generation, but it has passed on to the next and now it is even worse,” bemoans Jaber Mohammad, a 35-year-old businessman from Dubai. “We did our 12 years of schooling with normal Arabic and never used Arabish until we were in college, but now the younger generation start using it when they are in school,” he explains. “I see it with my cousins and my nephews – they all use Arabish – I doubt they even have Arabic installed on their mobile phones.”

Mohammad has a long history of promoting the use of the Arabic language and Arabic content online. In 1997, he helped to develop an early Arabic chat room that provided users with an on-screen Arabic keyboard that allowed them to type with their mouse. Since then, he has helped to develop Arabic literacy, football and medical websites and his latest project is tajseed.net, a not-for-profit initiative that seeks to promote the development of Arabic infographics. He is alarmed and mystified by the enduring popularity of Arabish, but is clear about the scale and the nature of its threat.

“Lots of companies in Dubai and Abu Dhabi might not care if you can’t speak proper Arabic, but you might not get the job if you can’t speak proper English. We’ll end up with a generation who aren’t even linked to their own language and Arabish isn’t helping. It used to make sense back at the time, but not any more.”

Omar Al Hameli is one Emirati who is determined not to lose his relationship with the language he describes as his mother tongue. The 25-year-old insists on using Arabic in all forms of written communication and thinks that it is “ridiculous to talk with other Arabic guys in English.” He readily admits however, that this marks him out as unusual among his family, colleagues and friends.

“I am the only one of my friends who is like this. Some use the mixed language, but some use only English and when they try to type in Arabic I always find lots of mistakes. Sometimes I poke fun at them and tell them that they should use their own language.”

For Al Hameli, an environmental science student at Deakin University in Melbourne, Australia, the correct use of Arabic is central to his sense of self.

“I hate it when somebody messes with Arabic because I love this language. It is part of my identity. The Quran is in Arabic and I am an Arab and a Muslim. I would love to do my Master’s in Arabic because I want to learn more about the language and I want to understand the holy book.”

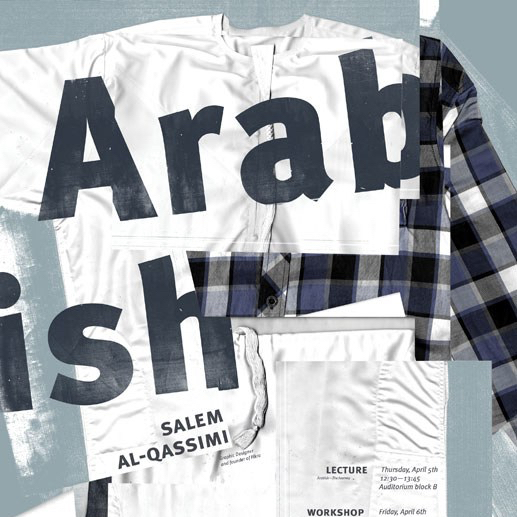

Salem Al Qassimi has rather a different perspective on Arabish, and is used to having to defend his views. “People have criticised me for advocating this way of writing, but I have never said that Arabish is good or bad.”

The 30-year-old designer and founder of the Fikra Design Studio in Sharjah started researching the cultural significance of Arabish and its impact on Emirati identity while studying as a postgraduate at the Rhode Island School of Design. Language is also central to his sense of identity, but bilingualism was something with which Al Qassimi has grown up.

“I went to an American school, an American university, and I was trained as a designer in English. There are certain design terms that are difficult to translate into Arabic, so I use English when I talk about design. At home with my family and friends however, I use Arabic, and if I am speaking about religion, there is no way I can translate that into English because Arabic is the language of Islam.”

For Al Qassimi, Arabish is something more than a matter of emails and text messages, it is a concept that has become central to his design practice and his whole way of life. Right or wrong, Arabish is a cultural reality that cannot and should not be ignored.

“Right now, I feel that we live in a hybrid culture and Arabish is a philosophy about the merging of cultures. The way we dress, the cars we drive, the lifestyle we carry, all of those confirm Arabish as a fact.”

The cultural and linguistic hybridity of Arabish is something that Al Qassimi investigates through graphic design, typography and film, media that come together in projects such as Typographic Hybrids in the City, an animation that sees Arabic letters and their Roman replacements fly across the cityscape of Dubai, set to a soundtrack that mixes classical Arabic oud music with modern electronica. In Hybrid Dress, Al Qassimi created a series of posters that overlaid a kandura, the traditional clothing of Emirati men, with Western shirts and jeans and the words “Arab” in Arabic, and “Western” in English.

Rather than trying to resist the kind of cultural change that Arabish represents, Al Qassimi believes that it should be embraced, not only because it is inevitable, but because it also denotes an openness and a vitality in contemporary Emirati culture that he believes are necessary and that should be encouraged.

“To identify Emirati culture today as something that it was 50 years ago is incorrect. We are creating our own culture and a new identity right now by taking the identity we had previously and building on it, but if we restrict ourselves by not absorbing or taking things from other cultures, then our culture will become stagnant.”

“Will English affect our local, colloquial Emirati Arabic? For sure. Is it going to affect formal, classical Arabic? Not so much, because that is the Arabic of the Quran and we will always go back to that. It is the biggest protector of Arabic that we have.”

If the use of hybrid text and language has assumed the status of a moral panic in discussions about the fate of the Arabic language – a term used by sociologists to describe phenomena that are perceived as threats to cultural values and social order – there are Arabs who are campaigning for a brighter future for written and printed Arabic.

The Lebanese designer, academic, and writer Huda Smitshuijzen AbiFares is one of these. As the founding creative director of the Khatt Foundation, a largely virtual cultural organisation and network of experts, designers, and researchers, Smitshuijzen AbiFares has been responsible for organising a series conferences, exhibitions, books and workshops dedicated to improving the quality of contemporary Arabic typographic design.

Her vision is nothing less than the regeneration and the renewal of Arabic visual culture – something that she currently defines as “poor” – and her aim is to achieve this using the medium of Arabic type. “Our main goal is to talk about a constant rejuvenation of the culture through typography” she explains.

“It’s important that we look at our script. In Arab culture, two of the highest forms of art we have are calligraphy and poetry, but we no longer see these in our public spaces and our cities. That is a loss.”

Smitshuijzen AbiFares has been in Dubai for the last nine days, coordinating a series of daily, nine-hour-long practical workshops in Arabic calligraphy and font design. Despite its gruelling workload, the course, the third of its kind to be held at the Tashkeel studios in Nad Al Sheba, has succeeded in attracting a dedicated band of delegates from across the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Europe and the United States.

The quality of tutors, internationally recognised luminaries such as the Syrian calligrapher Mounir Al-Shaarani and the specialist Arabic type designer Lara Assouad Khoury attract some. Others are drawn by the prospect of producing their own unique digital font, no small matter in a world where the number of Roman fonts outnumber their Arabic counterparts by more than 100 to one. The course’s biggest pull however, is its rarity, as Smitshuijze AbiFares explains.

“Arabic type design has not been properly covered in design education, especially in the UAE. There are graphic design courses, there are typography courses, but Arabic specific courses are lacking. Even elsewhere in the world, these kind of courses are not widely spread.”

“We need these courses in the Middle East because we do not have enough well-crafted, good quality Arabic typefaces. I have a class full of Arabs, but every one of them speaks a different Arabic. That should also be seen in the way they design.”

For Smitshuijzen AbiFares however, the main obstacles to the cultural rejuvenation she seeks are not only a lack of knowledge and expertise but something more profound, an over-protectiveness of Arabic that stems from a lack of self-confidence among Arabs.

“There’s a sense that we do not know how to define ourselves because everybody tears you in different directions. If you try to do something new, everybody automatically labels it as Western, but if you do something traditional, it doesn’t quite relate because you’re dealing with something that comes from a thousand years away.”

For Smitshuijzen AbiFares, the success of the Khatt Foundation’s project relies on the development of tools that will enable designers working in Arabic to develop a contemporary and authentic voice of their own, independent of Western firms, commercial concerns, and unfettered by what she sees as a widespread tendency to constantly revisit and refine things from the past.

“There’s a misunderstanding that being contemporary is not being Arab,” she explains. “I don’t believe we should shut other cultures out, not at all, but instead of just absorbing everything that comes from abroad, just because it comes from Europe, [that] is a bit strange … Our culture is not dead and I don’t believe we need to preserve it, but to evolve it and to nurture innovation. That is the best way to ensure our culture goes on.”

This article originally appeared in The National, Abu Dhabi